A Useful Book and Some Thoughts about Debate

The Future of Capitalism - a Munk Debate (Anansi, 2020)

I just read the Munk Debate on The Future of Capitalism, and came away wanting to share some thoughts. I think the topic is something that teachers should be thinking about, because we’re going to be asked for our opinions by students – and if we don’t have anything but automatic answers, we will delay progress. And time is pressing. I also want to share some thoughts on the debate form as a learning tool.

I’m no capitalist; I’m hardly economically-minded at all and lean towards sharing, given a choice. I feel I’ve watched throughout my life a process of degradation wrought by the capitalism of the1980s until now: a degradation of language, of shared values, of institutions, of common spaces, and the reduction of people into brands and interaction into transaction. It has seemed shitty and mean all along, and has resulted in some profoundly foreseeable catastrophes. I’m confident about my interpretation, and it is abundantly clear that I’m not alone in thinking something needs to change or break.

My personal learning goal right now is to understand the side I don’t naturally agree with, or to at least hear from them in a reasonable (reasonable!) conversation.

The Future of Capitalism

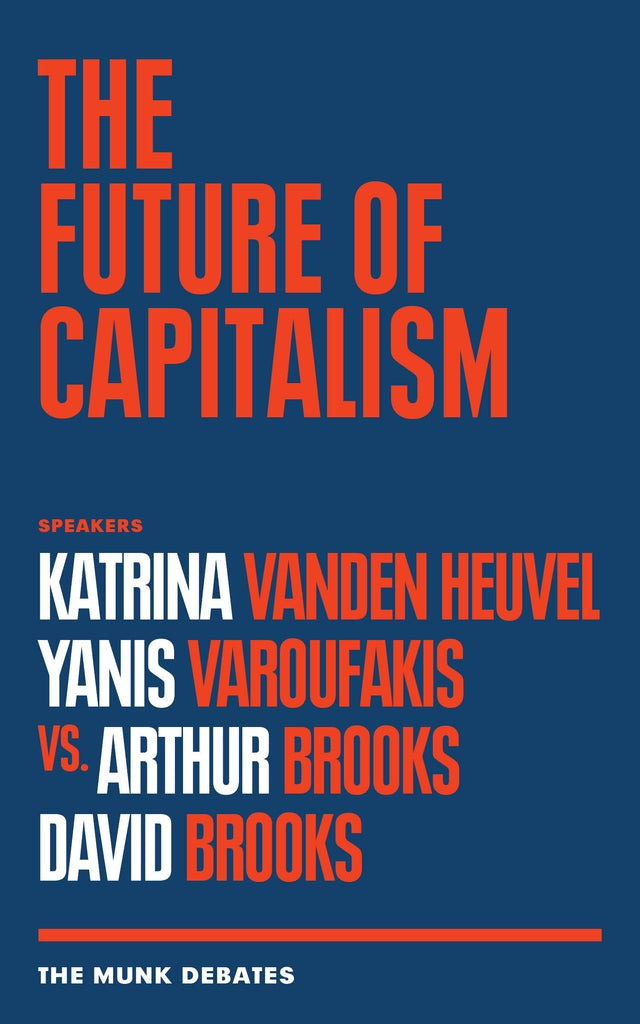

So I picked up this book – from the Toronto Public Library, thank you society – called The Future of Capitalism, which was a Munk Debate, featuring:

Katrina Vanden Heuvel

Yanis Varoufakis

vs.

Arthur Brooks

David Brooks

The Munk Debates are a semi-annual series of debates on major issues held in Toronto, usually by big names, which are then published as books by House of Anansi press. The debates are named for the organization’s founder Peter Munk, a capitalist who ran the world’s largest gold mining company but would prefer to be remembered as a philanthropist.

It’s a quick read. If you want a summary of what is being argued about under the umbrella of questions about capitalism, this is good - all the debaters are very informed and they’re sharing their clearest ideas: Capitalism deserves credit for the good it has done the world during its time, and capitalism is out of control and killing the planet. Basically.

I myself only read the debate itself; the book also has pre- and post-game interviews. Don’t rely on my glib analysis. Here is a transcript you can read, and here is a video you can watch.

But I came here to talk about it from a different perspective. I want to talk about the form and purpose of debates.

Debates

I have never liked debates - I have always preferred collaborative conversational arguments – but I can see how both have strengths and weaknesses. A good debate has rules that can be followed, the same way that a worthwhile meeting has rules to follow. Conversational arguments can sprawl, become personal, stray off topic, and have no ending – they could use some form.

But debates have a mandatory combat style – idea versus idea! – and a winner, which, while possibly being motivating to some, is a lower goal than understanding. I don’t think it would hurt the world to raise the calibre of discourse at a university auditorium. Conversational arguments allow for agreement and compromise.

A Different Debate

Back in the early 2000s, I joined an organization called The Long Now foundation. It was a project started by Stewart Brand and Brian Eno, and took as its fundamental idea that we should try and consider longer periods of time than we do naturally.

It’s the kind of intelligence hack I really like – the kind of perspective change that can be undertaken on purpose, and which has a potential positive impact on a lot of things. It considers, or tries to consider, the period of 10,000 years back to 10,000 years forward, and then has regular lectures and discussions in San Francisco that are available as podcasts. Very interesting. (I just read, while researching, that Bezos is now involved with their 10,000-year clock project. Don’t let that stink up the notion.)

But the biggest takeaway for me was the healthy “debate” format they employ. If The Long Now has two people batting an idea around on stage, they have the following format (from Wikipedia):

As part of the seminar series, there are occasionally debates on areas of long term concern, such as synthetic biology[13] or "historian vs futurist on human progress".[14]

The point of Long Now debates is not win-lose. The point is public clarity and deep understanding, leading to action graced with nuance and built-in adaptivity, with long-term responsibility in mind.[13]

In operation, "There are two debaters, Alice and Bob. Alice takes the podium, makes her argument. Then Bob takes her place, but before he can present his counter-argument, he must summarize Alice's argument to her satisfaction — a demonstration of respect and good faith. Only when Alice agrees that Bob has got it right is he permitted to proceed with his own argument — and then, when he's finished, Alice must summarize it to his satisfaction."[15]

Mutual understanding is enforced by a reciprocal requirement to describe the other's argument to their satisfaction, with the goal being more understanding after the event than there was beforehand.

The contest, unneeded, is neutered, and the content of the two minds (and all the other minds they’re channelling) is shared. There is no mandatory agreement - just mandatory good-faith communicating.

Not Cooperation! Nooo!

In the 1970s there was a well-intentioned educational move away from cut-throat competition and towards cooperative games; it is now regarded as a dopey half-solution that made games less fun. I am not suggesting that we make these conversations less rigorous, or that we allow untruths and nonsense to pass like a bunch of Joe Rogans.

I am suggesting that the point of intellectual discourse is not to play games, but to think together – and a game may not be the most effective way to think together. I am also suggesting that a good conversation with people trying to hear each other’s points as they strive collectively for correctness and a common increase in understanding and knowledge and creativity is actually super fun, in addition to being powerful and useful.

In the traditional debate model, opportunities for agreement are lost. When they are allowed to exist, they are usually a preamble for a parrying thrust or clever turnabout.

Yes But But But Yes

In The Future of Capitalism, the battle-performance is based around one statement that is either correct or incorrect. Be it resolved: The capitalist system is broken. It’s time to try something different… (Why it ends in ellipses is not apparent to me. Boomers.)

All four of the participants then weigh in with their observations and beliefs. They’ve got a variety of perspectives, all good to consider – and, shockingly, they all turn out to agree on the important stuff! Over time they all admit that things need to change, and they’re mostly only using different words. (Because it’s pretty obvious.) Capitalism is currently a mess, they agree: it is having destructive effects, and something has to change. Four minds, all more or less in agreement, and the format of the debate takes the opportunity and squanders it for sport.

The debaters have to challenge each other, so they challenge each other on minor points: Q: Is it something wrong with capitalism? A: Weeeelll, capitalism isn’t inherently X, so X is the problem, not capitalism! Capitalism has done great things, and terrible things – let’s move forward. No, no, we must not move backward. It’s sad to me. They’re compelled to find tiny areas to disagree with but are regularly agreeing with each other in the main. At one point they bicker, jokingly, over whether or not it matters which of them are from Canada. There’s almost nothing to argue about.

They agree with the things you probably agree with. Capitalism’s voraciousness is harming our planet, planned economies have not been successful, humans should benefit from human systems, freedom is important, unrestrained greed is destructive, some institutions should be held as common goods. The impending robot future needs to have its impacts considered and planned for. Corporate monopolies and mega-companies and banks are not good for society in any broad sense or long term. Innovation and motivation are important. Democracy shouldn’t be for sale. Good! Agreed!

Lost in the Weeds on Purpose

Capitalism – economies – societies – are complicated AF. People can and do spend lifetimes spinning around and playing with the elements of complicated AF texts – Talmudic scholars, James Joyce academics, QAnon idiots. It passes the time, fine – but it’s not worth much, not at a moment where something important must be done to fix an untenable present.

The Munk Debates paid to have these people speak (I assume), to put them up in hotels and drive them around so that they could be together in a room filled with audiences (real and virtual) who all care about what’s being discussed (I assume), which is one of the greatest questions of our age. And they treat it like a prize fight.

What if it had been different? What if, as the group agreed on certain propositions – like Capitalism Is Currently Harming the Earth – those propositions were put up on a screen, an ongoing We Agree on These Things list?

What if that list was used to propel a deeper conversation – not “should this thing we all agree should change, change?” but rather “Considering these points of agreement, how can we move forward? What useful ideas can we take out into the world after this discussion?”

What if instead of taking an audience poll of “whose mind changed” (a silly fake-science metric), the Munk Debates simply assumed that people who have gathered in a hall to listen to ideas will leave with something useful in their hat – because that’s how people work? Surely they know that the situation being discussed will require and reward collaboration?

Checking My Head

I asked my friend Blain to have a look at this piece, to check my biases. He’s also a teacher (professor), and a true academic thinker – a good balance for me. He shared that his own experiences on debate teams and with the form in general had been great, that he had enjoyed the rigour of the form and the practice in forming and stating arguments. Most interestingly to me, he pointed out the extremely practical applications the form provided for post-school life:

Also, since students are going to encounter people who make arguments as adults (politicians, colleagues, co-workers, etc.) it may be helpful for them to know the rules of the "game" and how to play it well. Debating (and "arguing" more generally, in the academic sense of putting forward positions with justifications, objections to other positions, rebuttals to objections, etc.) is a skill that I think more people should possess (not just lawyers and politicians), even if only to be able to discern the sophistry of others. (One of the professors for whom I taught while at Stanford would describe the "baby logic" – essentially rules for how to debate well – that we would teach undergraduates as a "bullshit detector" skillset.)

I get that, and agree. I had contended in an earlier draft that this skill was merely training for lawyers and politicians in amoral deception, but I had overlooked the importance of the skill. I tend to go hard at a target when I’m riled up - a defensive posture from a lifetime of hating school and of being dominated by “common” sense I disagreed with. Trying on an idea that isn’t yours helps you think about ideas structurally, which is a powerful ability.

I suppose my refined contention would be that formal debate training might best be seen as akin to the best martial arts training, which strengthens and empowers – and then requires restraint. The greatest martial artists don’t fight. The Munk Debates – the competitive aspect, the unavailability of agreement, the thumb-up/thumb-down voting – are vulgar to me in the same way that MMA fights are vulgar. There’s a place for them, but it isn’t a very high place.

Classroom Application

I am proposing that we, as classroom teachers, can make an impactful change in our classrooms by removing contests from things that are not contests. If you want to find out who is the fastest runner, have a race and congratulate the person on running so fast. But if you want to teach something, or discuss something, don’t wreck it by playing down to our base instincts and making it a contest. Knowledge isn’t a finite asset.

I am not suggesting contests are anything terrible. I am just suggesting that we must become aware of how they work on a meta level. A great basketball coach can train players to play basketball while keeping in mind that the skills involved are not only for use on the court. The shitty ones just want to win games, and give their attention only to the players who can provide that.

I recommend you try out the Long Now’s debate format - it’s really fun. And that you encourage students to try arguing positions they disagree with within that format.

Many thanks to Blain for his input, and as always, Marjan for her careful edit.

If you like it, please share it, and your thoughts.

Cheers,

jep