I started showing Children of Men (Alfonso Cuarón) the year that Syrian refugees were in the news all the time – 2015/16, just before Drumph’s election. Millions of refugees were fleeing destruction, Canada was due to take some smallish number of them, and people I knew – people who had themselves fled tyranny and come to Canada, or whose parents had – started “just asking questions” about how we’d know who was a terrorist and who was not. I was angry about this. Children of Men shows where that impulse goes. I thought showing it could help my students be better when their generation needed open hearts and borders in the future.

As a teacher, I try to keep my editorializing honest but mostly positive, even when I’m feeling bleak about the world. I’ve carefully avoided talking about the impending doom of climate change, only letting it out in “what can we do right here” and “when you start voting, remember” ways. But the closer the thing gets, the less I want to pretend we can do anything fast enough to avoid catastrophe. With the evidence of our inaction and inability growing, I’m now thinking about what I can share that will help kids deal with the impending disaster. “How to imagine sharing space with refugees” seems like a good one.

So I showed Children of Men, and despite its bleak vision, the kids loved it – because it is an incredible movie, endlessly re-watchable, and ripe for analysis. It is a rewarding film to study. It shows the power of imagination in filmmaking, and it shows the cost of xenophobia and the concrete decision that hope is in the face of despair.

Children of Men (2006) is by Alfonso Cuarón, who also directed Gravity (2013) and Roma (2018), among others. One year our class chose him for our Director Study, and we watched/studied all three. Children of Men is a post-apocalyptic story set after a biological disaster: nobody on Earth can get pregnant anymore. The world falls apart under this existential strain: systems collapse, states fall, devastation reigns. Inside Fortress Britain, things are sort of still running… sort of. There’s enough wealth to sustain an idle ruling class, and some of them try to collect and preserve artworks that no one will be alive to appreciate in less than a century. Within that world, a depressed and disaffected former activist is called upon to protect a young woman and deliver her and her secret pregnancy to a group who will keep her safe – and hopefully save the future. Pretty compelling.

Cuarón’s filming process includes long, complex shots whose choreography would scare off most directors, entirely new filming rigs and gear, and incredible stunts. Atop this are memorable performances by Clive Owen, Julianne Moore, Chiwetel Ejiofor, Michael Caine, and Clare-Hope Ashitey. The transformation of England into the nightmare near-future fortress is deep and depressing, and the entire film is stuffed with intriguing, world-expanding background details. Items on corkboards, out-of-focus characters, references to art history, the Bible, and other religious texts, and a great soundtrack all pull us way in.

If you’re wondering whether you need to already know these things before you teach the film, you do not. I did not. I loved the film a lot, and found it impactful, but YouTube video essays and analyses revealed the glory, and I show those before and after the film.

Establishing Shot

We are introduced to Theo (Clive Owens), given a news-item glimpse into the state of the world, and an urban terrorist explosion within a single shot taken in downtown London. Look:

The Greatest Car Chase I’ve Ever Seen

The characters are on a dangerous quest – to deliver the young mother to safety – and so chases and crashes and firey explosions have to be included. Thankfully, Hollywood didn’t make this film, so these elements are allowed to exist without becoming stupidly loud or ridiculous, and without diminishing the emotional experiences of the people in the cars. Within one very long shot, we learn the history of the ex-couple, get a fantastic ping-pong-ball trick, bullets, blazing barricades, a horde of attackers on foot, and a motorcycle crash:

The film allows for a discussion of CGI and special effects that are used to support the story, rather than to add sparkle. The cameras are down in the dust and spattered with blood, giving the effect of war correspondence rather than an action movie. CGI is used in combination with practical human effects for the wild scene of Kee giving birth – and all of this is compelling enough to keep students grounded in the question of tasteful use of special effects.

And the ending is strongly ambiguous – a nice foil to the sanitized wrestling matches of the Marvel Cinematic Universe (MCU). One’s take on it depends to a large extent on one’s temperament, and can be seen as one of hope or its opposite. The tone in class after the film ends is one of fulfilled catharsis, and quiet questions about the future, and maybe an application to film school.

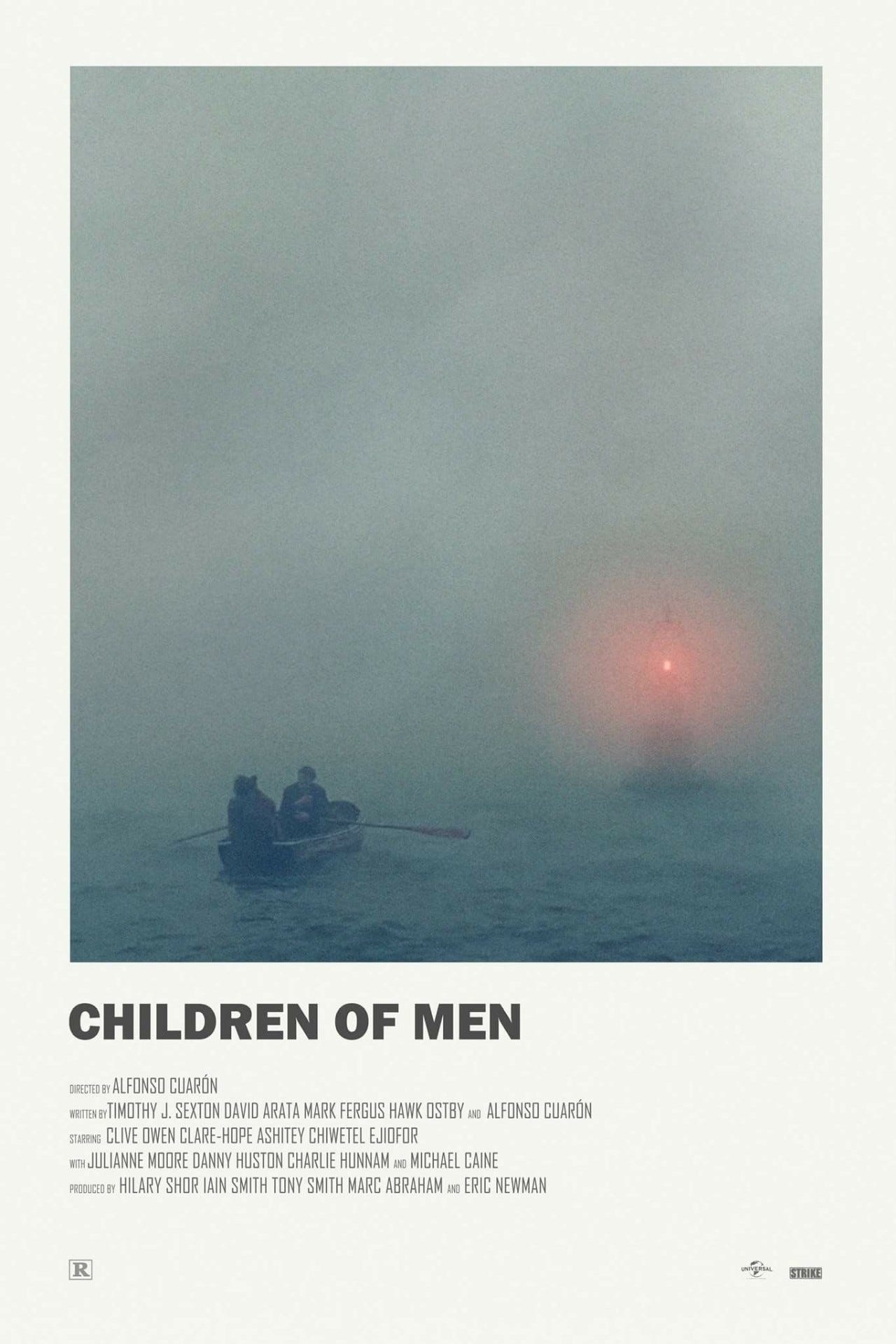

PS: Alt Film Posters

A large and interesting scene exists wherein designers and artists create alternative movie posters, prompted in large part by the terrible and lazy posters we’ve been enduring since the 1990s. I do not know much about it, but if you add “alternative posters” to your searches, you’ll see. If you have a class or a student to whom this might appeal, I can imagine fun alternative assignments, or crossover assignments between visual arts classes and film studies. Check these out and then go Google stuff.

If you have additional information or ideas to share, please do.

If you like this, share it.

Peace out,

jep