The Part Where I Get Lucky

I started working in the field of learning disabilities when I was 20, the summer after first year of university in 1990. Through flukes of luck, I landed a job at Camp Towhee in Haliburton, Ontario, run by the Integra Foundation in Toronto. I was absolutely unprepared, and I really had no reason to be there except that I needed a job.

It was an insanely fortunate opportunity, and it was well-timed. I had run entirely out of luck that year: I’d been kicked out of my father’s house, had dropped out of school, had a nervous breakdown that nobody noticed, and had just lost the job I had in a record store (I showed up for work and the store was gone, without a word!).

I was radically unprepared to be an independent adult. I not only had zero dollars, but didn’t even know about food banks, which I really could have used. Then I landed this job – I’d forgotten I’d even applied for it. I showed up at the camp’s bus with all my clothes in a laundry bin – I had no luggage or bags. Or shampoo. Or money. Or a hat, sleeping bag, or bug spray. I had contact lenses, but my glasses were busted, leading to an insane moment when I washed my contacts with straight lake water because I had no more solution. I was lost.

Going to Camp

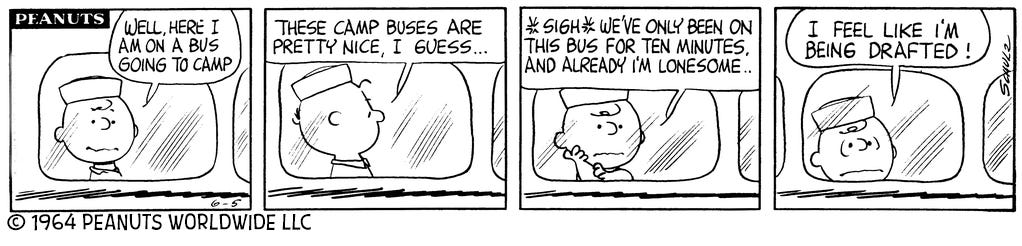

The place turned out to be a residential treatment centre, not a regular summer camp – and I had no experience even with “summer camps.” Nobody in Sarnia (my hometown) went to one, aside from maybe Scouts camp, and I was going to be a writer or a filmmaker, not a person who worked with kids. The only kid I knew who went to camp was Charlie Brown. And this wasn’t even a regular camp.

We were given a seven-day crash course in learning disabilities, as well as the stuff you need to know to work in a residential treatment centre. After an evening’s instruction on how to “do a restraint” with a kid who was, I dunno, gonna kill himself or something?, I was sitting alone, pretty stunned, on a porch. The camp’s art therapist, a woman named Jae, came and sat by me, and taught me a powerful life lesson.

“I don’t think I can do this,” I told her. “I’m not trained for this. I didn’t even realize this was what it was.” I told her the circumstances of my hiring: I had smoked a joint one night with Al, who was on the Towhee staff, and as we chatted, stoned, he announced, “You should work with kids!”

Three weeks later he burst into my dorm room – I was asleep – and demanded I give him a resume, because he was “heading in to Integra” and wanted to get me a job at Towhee. I typed something out in a bleary haze, not really understanding what was happening, imbuing the resume with my typical informality and attitude, gave him this stupid resume, and went back to bed. It might as well have been in crayon. I didn’t get a call. I didn’t even wonder if I would.

And then, two days before camp was to start, I got a call. Somebody had bailed on the job, they were desperate, and they asked me in for an interview. I left my drunk roommate out in the waiting room with a bag full of beer. And somehow the interviewer dug my vibe and outlook – I was overly honest, but had some impulses and experiences that fit well enough. When they called later to hire me I laughed and laughed, and took the job.

And here I was: out of my depth, clearly not “camp people,” with no idea why or when one might “restrain” a child. “Should I just go home?” I asked her.

Jae was the kind of person who can help by just hearing you. She sat there for a bit, and then said, “Well, you can, you know,” and then let me know she liked me there and thought it would work out. It was profoundly empowering to me, perhaps the first time in my life that someone let me know I was in charge of it, and that whatever I chose was okay, more or less.

So I stayed, and things did work out, and I began to learn about the many ways learning disabilities could impact a life. I haven’t seen Jae in 20 years or more, but I still love her for her gentle power. I try to pass along that favour whenever I can.

Good at Weird Kids

I was good at it. I’m good with kids, kind of naturally – especially weird kids. I had hated being a child, had felt unseen and unheard, so I purposefully treated kids in the opposite way. I found them funny and interesting. I was sort of primed, by accident, to be good at the job.

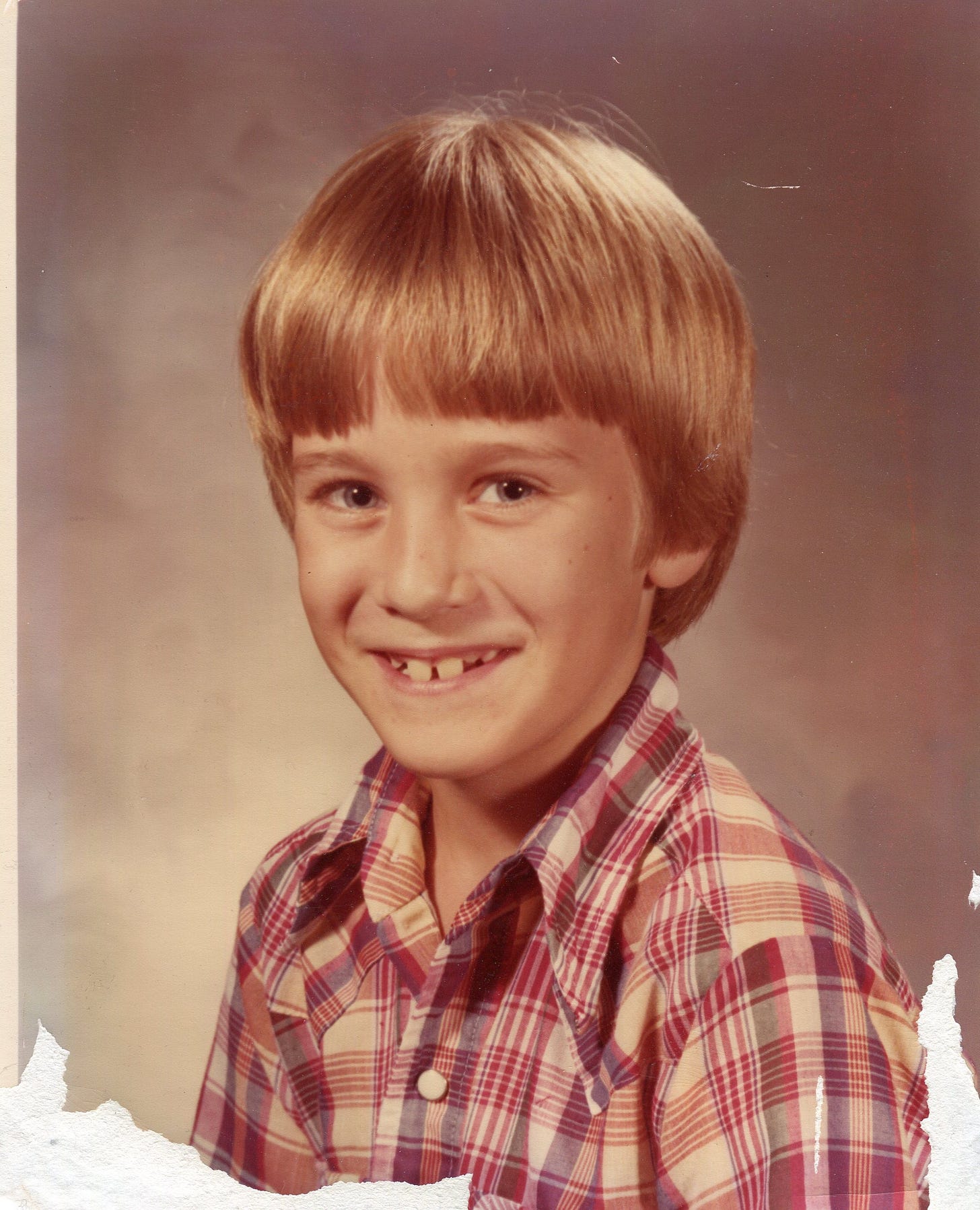

Me in School = Weirdo

My report cards always said I was not meeting my potential, that I could if I only “applied myself.” Every goddam one. Most of my teachers kind of hated me, at varying levels of intensity. Some years I was in trouble constantly; other years they’d put me into “gifted” (for about ten minutes). I was not gifted. They didn’t know what to do with me. I was just a weirdo.

I wasn’t rude or mean, I didn’t steal or beat people up or cheat – mostly I got in trouble because I liked to laugh and make people laugh. I did not care – hardly ever – about what we were learning. I spent almost all of my public education opportunity being confused as to why we had to go. I learned, but not because of school. Not even mostly at it.

Almost nothing I cared about happened at school: I liked music and comedy and comics and reading (good books) and movies and making stuff and fucking around. I was clever enough to cruise through school on Cs, taking my lumps in math and science, where I was a Known Idiot. I only ever “applied myself” in grade 13, and only because I knew that going to university was how one could get out of Sarnia.

But all of that meant that I was “good” with kids who hated school and adults, because I got it. I gave kids respect, and space, and when I learned a strategy that could help them communicate or flourish or be, I added it to my tool belt. I was profoundly fortunate to have bosses at Towhee/Integra who saw that, and saw that it was worth something. I credit them with saving my life. I had been lost, and now I had a place where I was appreciated and could contribute. People need those things.

Prepped for Weirdo Kids

The other piece of this personal puzzle was my family. Firstly, I have one little sister (of two, both awesome) who has an unusual mind. She’s adopted, and her in-vitro experience was brutal, developmentally – she was pummelled and beaten in the womb by drugs and alcohol.

My mother adopted her after reading a story about her in the paper (my father was there, I guess), and so we grew up together. She is six years younger than me, so we never fought about anything, and got along well – she liked music too (she’s a sort of prodigy, really), and was funny AF, and super-nice. Still is. I helped her with her schoolwork, and was comfortable with her physical needs and learning personality. So I was a bit primed to understand unusual minds.

Secondly, my childhood also included a fustercluck of an adoption that did not “take” – a boy who was my little brother for one year, a poor little abused boy who by five was filled with rage and addicted to negative attention, dysregulated, and powerfully spirited. My parents were absolutely out of their depths, and apparently everybody around them was ridiculously incapable of helping. The story ends with my parents sending him back - out into the wild, back into foster care. As in any good crime=curse story, we paid a price. The experience ended my family in many ways.

So I was also primed to understand and want to help angry kids who didn’t know they could be happy yet.

Learning about Learning Disabilities

Working at Camp Towhee and then at Integra’s in-Toronto programs, I learned all about learning disabilities. I loved this four-year period of my life – I found real purpose and friendship there. It led to all of the opportunities afterward, in one way or another.

Let this be a lesson to you. If someone offers you a joint, say yes. No, no, that’s no good. There’s no lesson. Sometimes you can get lucky, that’s all.

Learning disabilities (LDs) were a newish concept in 1990, and they were a goldmine for me, as they explained a lot of what had perplexed me forever about school, and people. Since 1990, they’ve become much more widely understood, but because they are a construct, they have morphed a lot over the intervening 30 years. I will try to explain, but it will probably take more than one try.

Learning Disabilities

At the time, people were pretty defensive about LDs, and always started their explanations by making it clear that they were NOT talking about kids who were, you know…

(Whispers: Intellectually delayed.) More on this at a later date.

Kids who had learning disabilities were “regular kids” who had “one or more areas of significant impairment” in school stuff. (I will be moving between casual and even flippant language and serious language, because I do that and it doesn’t really matter. More on that later too.)

A kid could, say, do really well in school but also have problems reading. That kid might have dyslexia, which you’ve no doubt heard of. The gist of the new knowledge then was “That kid isn’t dumb! They just need help with reading, or some aspect of reading.” They needed to be taught correctly, and then they’d be fine. They could “even go to university” (then the goal of any well-off family).

Well-Off Families

Well-off families were key in this new push for understanding. Today, three decades later, it is still true that poor or disenfranchised kids who have LDs are often labeled “bad” and weeded out of school (and often into the prison-industrial complex). At the less extreme end, kids with significant LDs are labeled correctly in public schools, but then given band-aid solutions that only sort of help, sometimes, when the resources are there. It is amusing and problematic to me that my work tends to serve the well-heeled. More on that later, I’m sure.

But this wasn’t some conspiracy (anymore than our hidden caste system is always a conspiracy): well-off families have the time and resources and expectation of success that are needed to champion the needs of the vulnerable. Camps like Towhee and schools like mine were all kick-started by activist parents, starting in the 1970s, and they are good, wonderful, essential places. There need to be more of them, publicly funded, everywhere. That kid with dyslexia should, in a functioning education system, never have been made to feel stupid. The wasted human potential is a tragedy.

Other learning disabilities could affect one’s ability to process language, or spatial awareness, or comprehension of facial expressions, or organization, or attention span, or control of impulses. All of those LDs have been given names at times, and have then morphed or combined or been categorized differently.

At one point LDs and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) were connected but not the same, and autism was a whole other thing. ADHD has been confidently written as AD(h)D, ADD (inattentive), ADD (impulsive), and the regular ADHD, and has included a wide and changing swath of attributes over the decades. (A quick search taught me just now that “There Are Seven Types of ADD/ADHD,” as well as some new and exciting terms: ADHD-C, ADHD-NOS, ADHD PH-I. I’m not going to investigate further – I think they’re trying to herd cats.)

At one point non-verbal LDs included traits that are now “on the spectrum.” Working with one child over about four years, I saw his diagnosis changed from autistic to Asperger’s to non-verbal LD, with no change in the child beyond growing older. Asperger’s itself – often used to refer to (I apologize for this term) “high-functioning autism” – turns out to have been named for a child-murdering Nazi doctor, and must be re-termed right now.

I’m not pointing any of that out to denigrate anybody’s efforts (except the Nazi doctor), just to make clear that these descriptions of unusual learning attributes are a construct that we are still constructing. It is to that end that I will continue to explore how we conceive of them, and how – I think – we can construct a more useful, more respectful, and more honest way of thinking about Weirdo Minds.

A Quick Note about the Term “Weirdo”

I am aware that I’ll piss somebody off with my use of the word “weirdo,” but I can explain myself. One, I love it and have long identified myself as a weirdo, with pride. This started with a beautiful comic by Lynda Barry – part of which I have tattooed on my body – from 1993. In it, one weird kid comforts another weird kid by demanding he see his individuality as a gift and not a curse.

Two, I feel confident that the race for every weird thing to be fitted into “normal” is a big mistake. “Normal” is a gaslighting concept that nobody actually ever fits into, the way fashion magazines use “beautiful” to mean something you must, but cannot, become.

If the term bothers you, please consider getting past it. At least forgive me. You have more important things to worry about. In my dream universe, the wonderful Mister Rogers would have written – in addition to the rest of his gifts to the world – a song called “It’s Good to Be a Weirdo.” Maybe you could write it.

Coming up next in this series: streaming and dignity.

Til then, remember my man Mister Rogers’ words:

“In some ways, just by being a human being, each one of us is very, very fancy.”

- jep

More from A Different Fish:

Great post. What an inspiring (and funny) "background story"!

These are awesome, please keep writing them.